There is, perhaps, no place on Earth so supremely well suited for high-speed rail as the leeward side of the island of Formosa. Sheltered from the Pacific winds, all of Taiwan's major cities hug the island's western coastal plain, unbroken by the mountains that characterize the interior. Running in nearly a straight line, the train covers the 214 miles from the Taipei to Zouying in two hours. It now carries 44 million passengers per year. Intercity air travel has been halved since the line's opening in 2007.

California is not Taiwan.

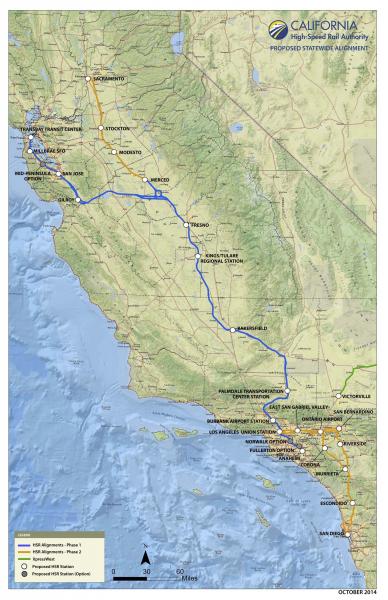

For all the years that California has debated high-speed rail (HSR), I have wavered between excitement and dread, optimism and resignation. My visit to Taiwan two years ago, when I learned that getting from one end of the island to the other is almost as easy as stepping into an elevator, made me fall in love with the technology and, simultaneously, convinced me that it would never arrive in California. Taiwan's system, at a little less than half the length of California's proposed system, cost $18 billion.  We are bigger than Taiwan, and our cities, though they are nominally coastal, do not line up obediently, like schoolchildren on a playground. They hide behind mountains and in bays. They have built battlements in the form of freeways, aqueducts and conventional rail lines, bringing people (and water) in but crowding out anything new. They are surrounded by proud agriculturalists and rabid lawyers. The alignment is a shapeless mess, with a less-populated midsection that makes the line an all-or-nothing proposition.

We are bigger than Taiwan, and our cities, though they are nominally coastal, do not line up obediently, like schoolchildren on a playground. They hide behind mountains and in bays. They have built battlements in the form of freeways, aqueducts and conventional rail lines, bringing people (and water) in but crowding out anything new. They are surrounded by proud agriculturalists and rabid lawyers. The alignment is a shapeless mess, with a less-populated midsection that makes the line an all-or-nothing proposition.

Anyone who has taken a Shinkansen, TGV, AVE, or any of China's 12,000 miles of HSR knows the wonders that await California if we get it done. This vision is the most optimistic justification I can think of for the groundbreaking that took place Tuesday in Fresno.

There are reasons to support HSR other than mere transportation, of course. Construction unions want the jobs created by the $68 billion investment. Gov. Jerry Brown wants his legacy. Fresno wants to be noticed. The feds want their money spent. Only a fraction of the system has been funded, but it's plain to see that the groundbreaking is meant to lend an air of inevitability to the project. The only thing more embarrassing than giving back $10 billion in bond money and $3.2 billion in federal money (if either was legally possible) would be to spend the money and end up with $13.2 billion of useless track. So, supporters hope that, by hook or crook, the digging that began today will not cease until the shovels reach San Francisco and Los Angeles. It's the Golden Spike in reverse: start in the middle and work your way out.

The cities in question now face their own inside-out propositions. It's up to the California High-Speed Rail Authority to bring trains to the cities, but it's up to cities to decide what to do with the trains once they arrive. The one major shortcoming of Taiwan HSR is that its stations are located like airports, on the outskirts of their respective cities. California HSR has been sold to cities as a driver of urban revitalization, with stations -- many of which already exist -- in the centers of cities. Stations include Los Angeles' Union Station and San Francisco's Transbay Terminal (currently being rebuilt), as well as downtown stations envisioned for San Jose, Fresno, and Bakersfield.

Between now and the line's scheduled opening in 2029, these cities now face a planning challenge of generational proportions. Imagine tens of millions of people annually spilling into and out of trains fresh from the far ends of the state? They'll need hotels and restaurants. Businesses will want offices nearby so their executives can speed up to meetings with Google up north or with Disney down south at a moment's notice. They'll want to beef up their public transit systems to distribute HSR passengers throughout the metro area -- and help HSR stations realize their selling point as anti-airports. This is transit-oriented development on the largest imaginable scale.

Of course, you can't not plan for high-speed rail. And yet... what if it doesn't happen? What if those tracks end in an almond grove and the $13 billion runs out? What if future cap-and-trade funds, earmarked by SB 862, aren't supplemented? Can cities reasonably invest untold amounts of time and money devising plans based on some seed money and Gov. Brown's convictions? Will developers spend a dime until build-out is 100 percent certain?

I suppose the good news/bad news is that, even if it goes according to schedule, HSR may not arrive in our lifetimes. Planners not yet born will have plenty of opportunities to gauge its progress and plan accordingly. If we were on Taiwan's coastal plain, I'd say it's a done deal. As I think about the Tehachapis, San Gabriels, and the Coast Ranges -- not to mention the $55 billion yet to be raised for the project -- I say, not so fast.