Nestled in a valley 12 miles north of Lake Tahoe, the Town of Truckee is known for its Old West history, ski-town vibe, and small-town charm. Facing growth pressures from tourists and residents alike, Truckee is, after years of resistance, about to get a little less small.

Truckee is small by geographic necessity. Its downtown occupies a narrow stretch bounded by Route 80 to the north and the Truckee River to the south. Historic Main Street – with its single-story red-brick buildings and false fronts – runs parallel to train tracks and stops short after just four blocks at an expansive 75-acre Union Pacific railyard.

With a population just over 16,000, Truckee is growing – and needs to accommodate that growth. But in Truckee, there simply isn’t space. But there is a railyard.

In the past decade, Truckee has embarked on an urban infill project that, by remediating a brownfield and building around a functioning railroad line, will transform a 156-year-old Union Pacific site into an extension of its historic downtown.

Based on a master plan first drafted in 2009, the Truckee Railyard Project will double the size of its downtown, blending workforce housing with commercial, retail, and civic spaces into a high-density, walkable city center. The project follows a statewide trend of downtown revitalizations, and many cities – most notably Sacramento – have redeveloped railyards or are in the process of doing so. But few, if any, have had to build around a functioning line.

“On the one hand, the infill project was intuitive because we had such a large vacant tract alongside our historic downtown,” said Denyelle Nishimori, Truckee’s Community Development director. “On the other hand, from a site layout and development perspective, you won’t find what we came up with at the railyard anywhere else.”

The 2009 master plan acknowledges the town’s affordable housing problem. For years, annual data had shown consistent economic growth: with commerce and tourism buzzing, tax revenue was steadily increasing year over year. This generated demand for new commercial and office space – and demand for new workers, too.

“Fifty percent of our workforce was commuting from outside the city. And over fifty percent of homes here are vacation residences,” said Alexis Ollar, Executive Director of Mountain Area Preservation, a local environmental advocacy group. “We take pride in being a town where everyone has a chance. But we were leaving the fabric of our community behind.”

The town needed to build – but they didn’t want to create any more sprawl. “We put preservation of our open spaces first,” said Nishimori. “That meant being proactive about growing in and up, and not out.”

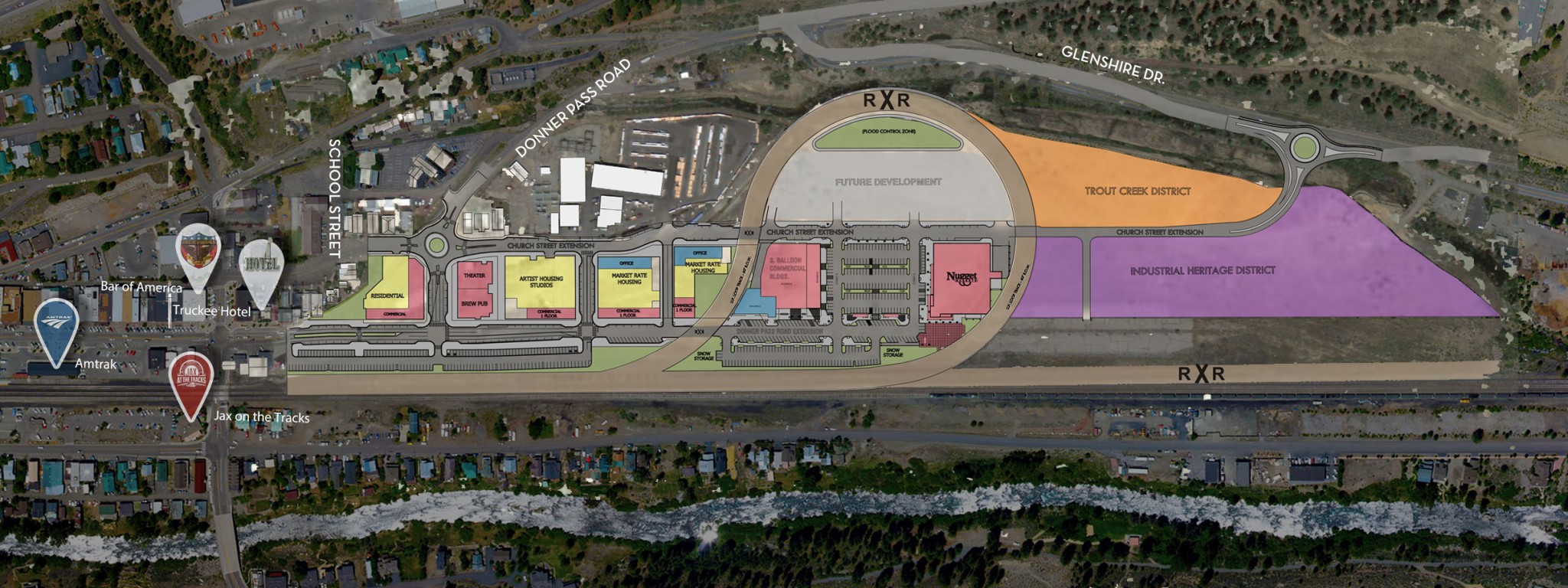

The town first approached the railroad about the site in 1997. Initially, Union Pacific wasn’t willing to sell the land. It still relied heavily on one track: a loop that enables the railroad’s snow removal engine to turn around at the end of the line. This so-called “balloon track,” which marks the eastern terminus of up to 180 snow-clearing trips per winter, traces a wide loop in the center of the site and encircles much of its usable space.

In 2004, the town enlisted Berkeley-based planner Rick Holliday to negotiate a deal with the railroad that would inform the plan’s unusual layout. After years of back-and-forth, Holliday made a brazen proposal: leave the track as-is, let the snow train continue to use its current path, and build the new development around and within it.

“You’re not going to find this balloon track in any other plan,” Nishimori said. “It creates a really interesting dynamic to plan around, and an opportunity to infuse different flavors into separate districts.”

Holliday did not respond to requests for comment.

Extending east from the historic Commercial Row, the plan separates the area into three distinct zones. The Downtown Extension District blends high-density commercial, residential, and community spaces across wide city blocks. The balloon track still occupies the center of the site, encircling a commercial and retail zone, including an already approved grocery store. Crossing the far east side of the track, a new extension of Church Street Road stretches to the residential Trout Creek District and the multi-use, live/work Industrial Heritage District.

The Downtown Extension’s first approved project is also its centerpiece: a 77-unit, four-story, mixed-income and mixed-use “Artist Lofts” housing development, designed by Holliday and CFY Development.

“From a social justice and equity perspective, putting workforce housing at the center of our plan was really special,” said Ollar.

Centralizing affordable housing may prove an effective planning, strategy, too. The Artist Lofts create an “affordable housing bank” for the zone. When a new commercial developer begins a project, they will receive credits from units in the Lofts toward their affordable building requirements.

“The affordable housing bank was a real innovation,” said Loux. “Developers are there to build what they want, not necessarily to meet affordable requirements. So those projects can end up languishing for years.” Such a bank would be the first of its kind in the Sierra region.

An animosity to sprawl goes back to the city’s origins. Settled in 1863 along a wagon route over the Sierras and then a waystation on the original Transcontinental Railroad, Truckee remained an unincorporated community of Nevada County until 1993. But with all decisions left to officials “down the hill”, residents noticed disturbing trends: resort-style homes encroached on the landscape, and strip malls threatened local small businesses.

In 1987, the county approved a K-Mart off of Route 80. “The K-Mart was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” said Loux. By 1993, the battle against K-Mart led to full municipal incorporation. Over the next four years, Truckee’s first-ever General Plan, with the railyard remediation and affordable housing at its center, took shape.

Still, during a years-long funding shortfall, it wasn’t clear whether building would ever begin. “We did our first master plan in 2009 at the height of the recession,” Loux said.

In 2015, the project received $8 million in cap-and-trade funding from the state’s Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities (AHSC) program. And, just this past year, the Artist Lofts received a nine percent low-income tax credit windfall from the state – after its third application for the grant. Now, with $14 million of infrastructure in the ground, plans are ready to go vertical.

To David Tirman, Truckee’s mayor, the project’s innovations are rooted in the spirit of a historic past: as recently as the 1960s, downtown Truckee was a vibrant pedestrian-focused center.

“Truckee’s future has found a roadmap by looking at Truckee’s past and the historic downtown, which was built around density and walkability,” Tirman said.

And that history began with the railroad: the original 1863 line that put Truckee on the map. As the town undergoes a General Plan update, they’re reminded of that history – and reflecting on the character of their community.

“As we update the General Plan, our goal is to stay true to what we value and who we are as a community, but to evolve how we use our space.” Nishimori said. “What we’ve imagined for the future of this railyard – a historic site, the place where it all started – well, there’s no better example of our evolution than that.”

Contacts & Resources

Jeff Loux, Truckee Town Manager, Jloux@townoftruckee.com

Denyelle Nishimori, Community Development Director, Town of Truckee, dnishimori@townoftruckee.com

David Tirman, Mayor of Truckee, dtirman@townoftruckee.com

Alexis Ollar, Executive Director, Mountain Area Preservation, alexis@mapf.org

Image courtesy of Town of Truckee.