It’s election season, and throughout California we are seeing an unusually large number of ballot measures designed to restrain development. As usual, most of these measures are in coastal areas. Some are urban growth boundary measures, but a lot of them try to put a brake on the density and/or height of new residential development. Presumably that’s because longtime residents in these coastal areas fear that high-density residential development will invade their communities.

But even as these skirmishes are still going on, it looks like the battle is over – at least in coastal California. Higher-density development has already won. And increasingly that’s creating a bifurcated state. New single-family homes are built pretty much only in the inland areas. With a couple of exceptions, the coastal areas are turning dense.

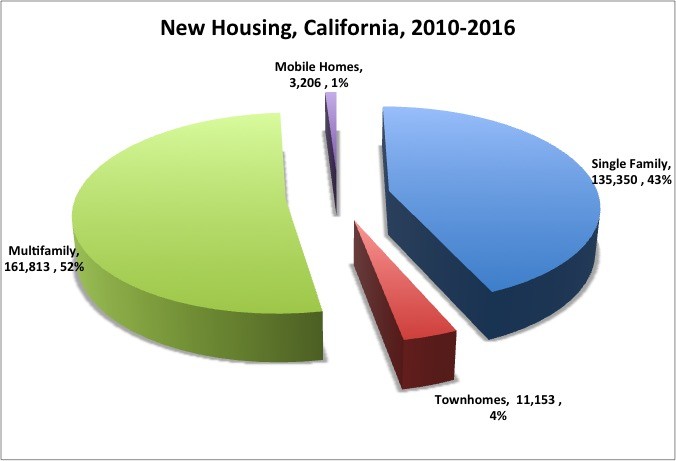

Perhaps most strikingly, the move toward multifamily development has gotten much stronger since the Great Recession ended. According to the Demographics Research Unit at the Department of Finance, between 2010 and 2016 more than half of all housing units built in California were multi-family units, and the vast majority of those were contained in projects of five or more units. This reverses the trend from the 2000s – but reinforces a trend from the 1990s. (All numbers in this article are derived from DOF's most recent E-5 spreadsheet.)

Now, there are a lot of caveats here. There hasn’t been that much housing built since 2010 – only about 300,000 units, or an increase of about 2.5%. (There was only about one housing unit built for every six people addd to the population.) There was a huge amount of single-family housing built during the real estate boom that ended with the crash in 2008 – much of which was available for rent or at cut-rate prices when the Great Recession ended. And lenders have been gun-shy about single-family subdivisions for years.

But the trend is striking. And it’s even more striking when you break out the coastal and inland areas – or, more accurately, the land-poor urban areas (which are mostly near the coast and good transit) and the land-rich suburban areas (which are mostly, but not exclusively, inland and away from good transit).

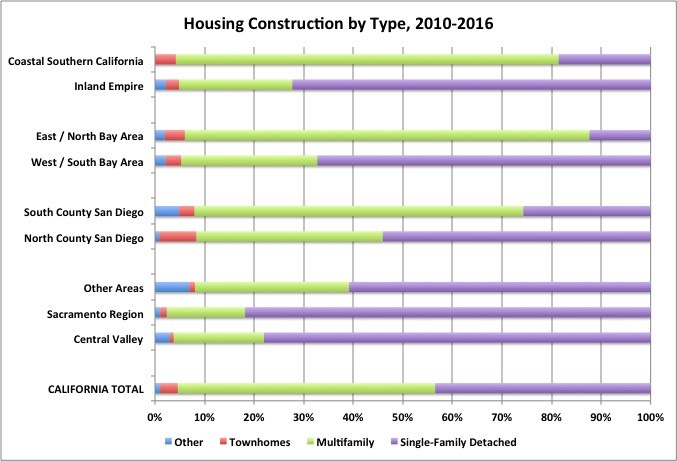

To see what I mean, take a look at the striking patterns contained in the chart below.

In coastal Southern California – Ventura, Los Angeles, and Orange counties – 77% of new construction is multifamily and only 18% is single-family. (Even in Ventura – land-rich but highly regulated – the numbers were 62% multifamily and 27% single-family.)

In the Bay Area, there’s a similar big divide. If you look at the rapidly urbanizing counties with good transit – San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Alameda – you’ll see that 83% of new housing since 2010 is multifamily and only 12% is single-family. In the other counties – Contra Costa and Solano to the east and the three notoriously no-growth counties to the north, Marin, Sonoma, and Napa – you’ll see that only 28% of new housing is multifamily and 68% is single-family.

We see the same thing in San Diego – though, as in the Bay Area, some of the single-family dominance is located in slow-growth coastal areas with land. In South County, 66% of new housing is multifamily and only 25% is single-family. In North County, 54% is single-family and 37% is multifamily.

But that’s not the whole story. There’s also a story here about big cities in California. Contrary to recent history, they are growing faster than the state as a whole. They are adding housing faster than the state as a whole. And they are adding multifamily housing much faster than the state as a whole.

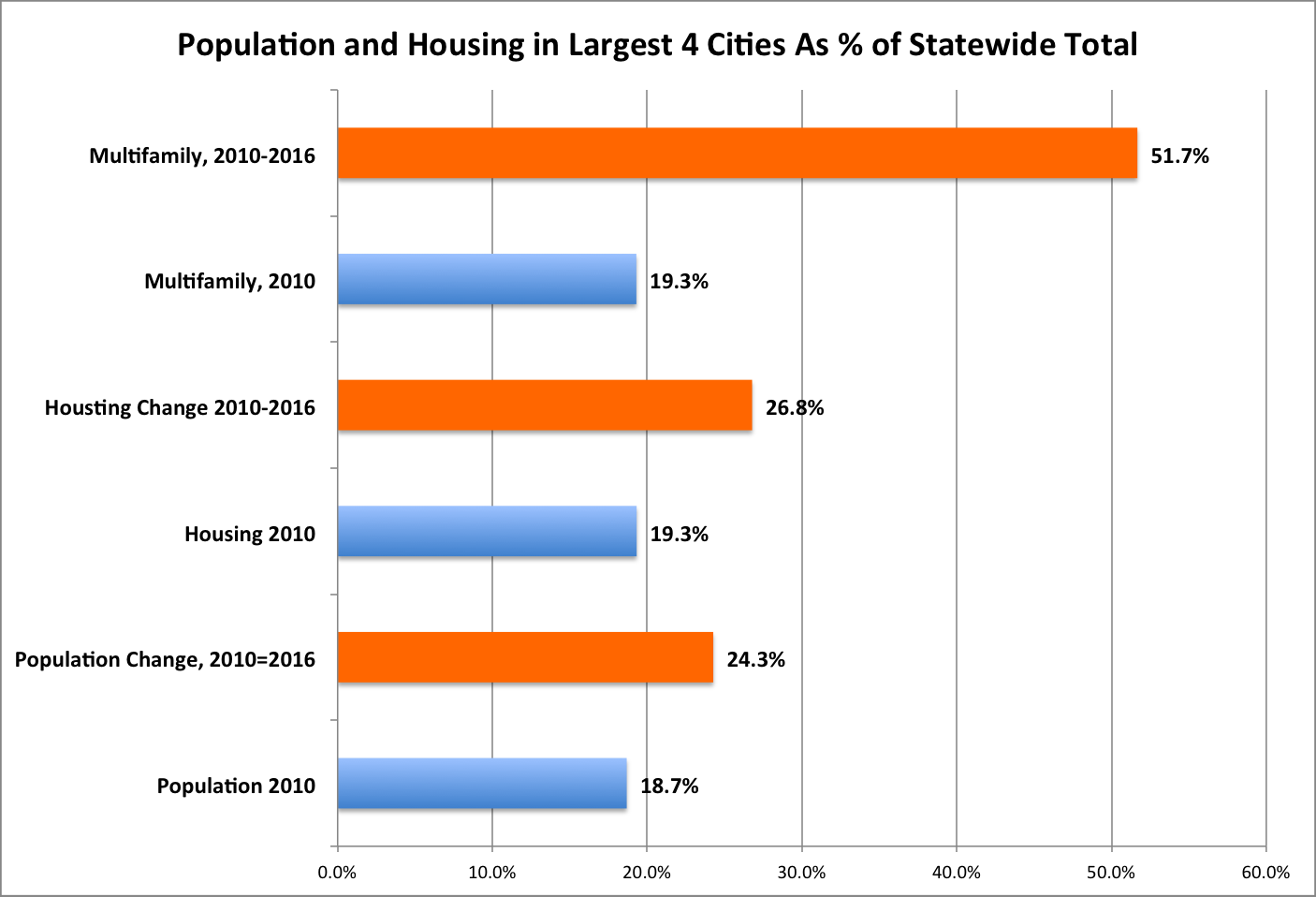

The trend is really striking with the biggest cities. Take a look at the chart below, which compares the four largest cities with the state as a whole. Bear in mind that three of the four cities – Los Angeles, San Jose, and San Diego – are geographically very large, while San Francisco is not. Those big three cities are, however, running out of land.

The raw numbers are striking. Of all the new housing built in these four cities, 92% was multifamily and only 7% was single family.

But the numbers relative to the state as a whole is even more striking. Look at the chart below. Blue represents the situation in 2010; orange is the change from 2010 to 2016.

In 2010, these four cities had about 19% of the population and 19% of the housing. But between 2010 and 2016, these four cities added 24% of the population and 27% of the housing. Most strikingly, they added about 52% of the multifamily housing.

In other words, more multifamily housing was built in L.A. San Jose, San Diego, and San Francisco than in the entire rest of California put together.

This trend plays out with other big cities, at least in coastal areas. Big inland cities are like their surrounding counties. Housing construction in Fresno, Bakersfield, Sacramento, Stockton, and Riverside – the five biggest inland cities – is all overwhelmingly single-family.

So there it is: Bifurcated California. One very identifiable part of California is getting much denser really fast. One very identifiable part of California is not. It doesn’t break out. This doesn’t break down perfectly by coastal and inland areas – political culture about land use in places like the North Bay and North County San Diego matter a lot – but the overall trend is clear.

In the long term, the question is not so much how the bifurcation occurs but what it means – not just politically but also in terms of policy, transportation, and lifestyle. For example, as the state’s push for a planning policy revolving around reduction in driving grows, the dense coastal areas will have a huge advantage in competing for money. And the big question is probably whether anti-density politics in the coastal areas will trump pro-density market trends. If the market wins, that means more housing built near job centers, lessening the transportation impact. If anti-density politics wins, that means more housing gets pushed inland. More people will be living in single-family homes, but they’ll be driving a long way to work. Whether they will be happy or not remains to be seen.