For the past century or so, two industries have both fueled Los Angeles’s local economy and defined its civic image: Hollywood and real estate. Now that both are faltering, I can’t help but consider some of their perhaps surprising commonalities -- and their woeful indifference to each other.

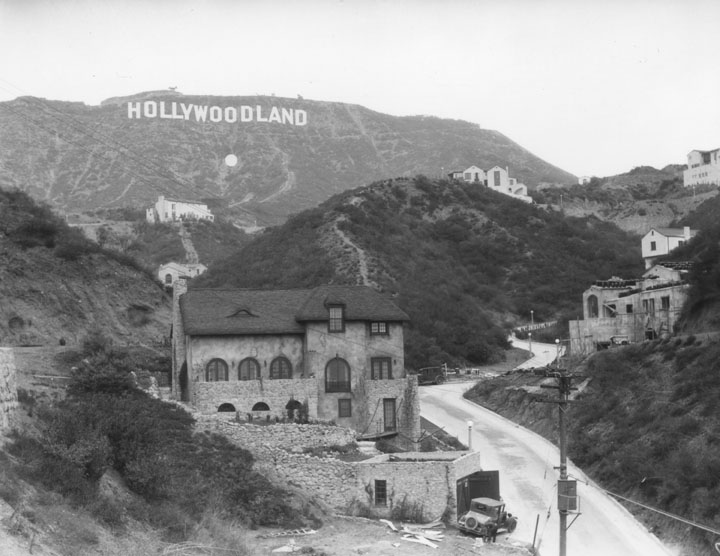

As many non-Angelenos probably don’t know, the most famous architectural symbol of the entertainment industry originally had nothing to do with Hollywood and everything to do with real estate. “Hollywoodland” was a 1920s housing development, advertised by a gigantic mountaintop sign. Eventually, the “LAND” fell down, and the movie studios stuck around.

Landmarks aside, what does entertainment have to do with real estate development? Superficially, very little. One is as tangible as they come, while the other flickers through thin air. One is near the very base of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, providing shelter. The other is, notwithstanding the banality of the Kardashians, a crucial component of self-actualization. One can yield ungodly profits or plunge companies into bankruptcy. So can the other.

For all of their obvious differences, these two industries are unusually kindred spirits. Consider the dramatis personae:

- Developers and producers instigate the project, create the broad vision, raise the money, and assemble the team.

- Financiers and investors, through often Byzantine arrangements, put up capital up-front, based on their assessment of trends, taste in source material, demographic research, and, perhaps most importantly, blind trust in their creative teams. Then they wait for returns.

- Architects and writers draft the projects, with varying measures of creativity and practicality.

- Engineers make sure the building stands up; cinematographers make sure the camera captures what it needs to.

- Contractors and their teams of craftspeople and laborers actually build the thing, turning blueprints into framing and drywall. Directors and their teams of craftspeople and laborers shoot the thing, turning scripts into performances and images.

- The top brass work out of trailers. Around noon, the food trucks show up for everyone else.

Fundamentally, entertainment and real estate must predict the future. Projects evolve on the order of years. They are capital-intensive, demanding up-front monies years before revenues come in, depending on the whims of consumers. Some projects appeal to urban aesthetes; others are family-friendly. Ultimately, audiences file into the theater or turn on the TV, inhabiting a fantasy for a little while. Residents and tenants move in, acting out their lives for months, years, or forever.

Let’s not forget about some big personalities. Egos rise when you build something 40 stories tall, or when tens of millions of people know your name. The question for the aspiring Los Angeles mogul is, would you rather be an Ozymandias or a Shelley?

These connections would amount to fun trivia if both industries were thriving. Alas, they are not -- at least not here.

Moviemaking in Los Angeles County is flickering out, with 31% fewer filming days in 2024 compared to 2020. This year is shaping up to be worse. Craftspeople are out of work. Support services like prop shops are closing. CBS recently sold Television City, its West Coast headquarters, which will be redeveloped. At least one entire studio lot -- the historic 20th Century Fox lot, now owned by Disney -- may be vacated, left to an uncertain fate.

It started years ago with "runaway production" -- shooting in Georgia, New Mexico, or Canada, rather than on local sets and locations with local talent – usually because those states and countries offer tax credits and other incentives. These trends have only accelerated with the fragmentation of media, the rise of DIY "content creators" and the placelessness of apps and streaming services. The industry's decline became particularly apparent weeks ago when, chillingly and bizarrely, Pres. Trump mused about putting 100% tariffs on entertainment created elsewhere. (How this would work is beyond me.)

Granted, a day of shooting in and of itself has little marginal effect on an economy as big as California’s. But, over time, other places have developed deep local talent pools and sophisticated infrastructure (such as Shadowbox outside Atlanta) on par with, or better than, any of the legacy studios in Los Angeles. It will probably always be the “entertainment capital of the world,” but the devolution of the industry means that the “capital” wields less power, and takes in less revenue, than it used to.

One of the reasons production "ran away" in the first place is that the cost of labor in Southern California is exorbitant. It's cheaper to pay gaffers in Atlanta and extras in Vancouver than to pay them for the same work in Hollywood. And why do local people need to earn so much? In large part because the cost of living -- and especially the cost of housing -- is manageable only if you're Bruce Wayne.

Housing development trends are in lockstep with entertainment trends. Despite RHNA numbers demanding that Los Angeles add over 400,000 units -- itself a large city -- apartment approvals in Los Angeles hit a 10-year low in 2024, with only 3,860 units approved -- half the number in 2014. Recent research out of the UCLA Luskin School is less than ebullient. Though Los Angeles recently adopted a massive housing-oriented rezoning program, called CHIPS, "Los Angeles will fall far short of its housing production goal" and will risk "displacement of vulnerable households" unless it supplements the rezoning with an "ambitious single-family upzoning policy."

All of this arguably was foreshadowed by a massive citywide downzoning effort that took place back when Shampoo was the city's defining movie. More recently, the Hollywood Community Plan--governing development in the actual neighborhood--has been the target of one of the city’s most vicious anti-development lawsuits.

It wasn't always thus. Cheap real estate made Hollywood. In previous generations, aspiring actors, craftspeople, and dealmakers gravitated to Los Angeles, living in flophouses, bungalow courts, dingy apartments, and pool houses. They didn't go bankrupt while they went to auditions and worked on their scripts.

They probably didn’t pay attention to civic affairs. But they should have. And they definitely should now.

On an annual basis, I attend more events related to planning and real estate that I can count. Panel discussions; keynotes; daylong conferences; mixers -- you name it. These events, repetitive though they may be, contemplate how the city should grow; how it should look; who should build it; who should pay for it; and who it should serve. This is heady stuff, and it's relevant to anyone who lives or does business in Los Angeles.

How many times have I run into someone from the entertainment industry? How many representatives of production companies or studios? How many agents? How many reps of unions or guilds?

Zero. Not a single one.

How do I know? Because I keep track. For years, I’ve hoped that, someday, someone would descend from the glitz and be willing to talk about what’s going on in the dirt. I keep waiting for someone in our city’s global, influential, once-wealthy industry to take even a passing interest in the health of the city. But, no. These people make Greta Garbo look like Ryan Seacrest.

The metonymy that is Hollywood has taken a woefully dim view of the all-too-real city that hosts it. Bigwigs who live in Bel Air don’t have to care about worldly concerns like workforce housing or civic pride.

The last time the real estate industry and Hollywood cooperated with each other was, as CP&DR Publisher Bill Fulton argues in The Reluctant Metropolis, in the development of downtown Los Angeles’s Music Center complex, championed by Buffy Chandler. That was in 1960. Since then, the prevailing indifference is a symptom of a frustratingly tepid civic spirit in Los Angeles. Life here has been easy for too many people and for too long. Now that it's gotten hard, we can either cooperate with each other, or we can retrench further. The latter isn't going to work out well for anyone.

The industry recently got some promises from Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass, and it has been lobbying for help from Sacramento, in the form of Georgia-style tax credits. All of that is... fine. But there's no incentive or tax break that could begin to compensate for the macroeconomic impacts of Los Angeles's bonkers housing market.

The question is, has Hollywood or the housing industry missed their cues? Have both entered their Norma Desmond phase? Not if they stop playing make-believe and start getting real.

Hollywood needs to wake up. Whatever the civic equivalent of a line of coke is, that's what the industry should be snorting. (Or, more elegantly, it needs another Buffy Chandler.) Then, it might want to apply its powers of messaging and persuasion to this crisis. The need for housing -- via apartments, ADU's, transit-oriented development -- needs to go viral. Ideally, Hollywood should promote exactly the type of neighborhoods that it likes to shoot. Movies and TV shows disproportionately portray busy, walkable, attractive urban neighborhoods (see related CP&DR commentary) that are easy to create on a studio lot but almost impossible with conventional zoning, financing, and infrastructure.

The entertainment industry needs to understand that a cheaper city will also be a more creative city, where artists can thrive without worrying so much about eviction or starvation. A more creative city means better (and maybe more profitable) shows, movies, music, and art.

As for what developers and, especially, planners can learn from Hollywood? Let’s face it: planners are, in general, not quite as dynamic as movie stars are, nor are they as tenacious as producers and agents are. A little of that swagger probably wouldn’t hurt. Developers already have it, but they often end up looking like bullies—the proverbial “greedy developers”—rather than partners hoping to realize a civic vision.

I know it’s become a cliche, but let’s also not discount the importance of storytelling—or at least of clear communication. Whether it’s a mayor articulating a citywide vision for development or a staff planner seeking public input into a project, the sense of drama, conviction, and eloquence that characterizes great entertainment can come in handy. Like actors who shoot 20 takes of the same scene or appear in 100 nights of the same stage play, planners must sell their performances each and every time.

Great actors, directors, and writers understand the histories and backstories of their respective performances, and they understand why their characters, plots, and themes are important. Developers and planners need to do the same: they need to understand how projects or plans fit in with greater vision for their respective places. The idea should be to win as many fans as possible.

Another thing these two industries share in common: making movies and building buildings are both exceedingly boring. They are long, tedious processes aimed at exciting results. They have that in common with public policy. But, I’m willing to bet that not making movies and not building are even worse. This is the moment when both of these once-great industries, with help from planners, need to recognize their common interests and flip this script.

Hooray for Hollywood(land).

Image credits:

California Historical Society Digital Archive, via Waterandpower.org.

Coolcaesar - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0