The panelists at the summit offered anecdotes and analysis — much of it excellent -- that would sound like old hat to most planners. To folks who haven’t considered the housing crisis and especially the influence of anti-growth stakeholders, it must have been terrifying.

- Scott Laurie of the Olson Co. described the woes of a developer. He described a 58-unit by-right project in the City of Orange that, though it conformed to the zoning code, got cut in half because of the objections of a single neighbor. Then there’s a project on the San Gabriel-Rosemead border. The Rosemead City Council told him up-front that it would nix its portion of the project if a single constituent objected to it. Guess what happened there.

- Assemblymember and former Santa Monica City Councilmember Richard Bloom said that would-be housing developers are bailing out and selling sites to commercial developers because — for reasons that defy logic — neighbors don’t protest commercial but treat residential like it’s toxic waste. “There’s this idea that housing doesn’t pay,” said Bloom. "Commercial pays.” This, despite the fact that residential typically generates less traffic.

- Carol Galante, former Federal Housing Administration official and current professor at UC Berkeley, said “it’s hardest to build where the jobs are” and summed up the situation neatly: “the way we do land use in California is not normal.”

McKinsey, of course, has some recommendations for normalizing the situation. Normal to the tune of 3.5 million units by 2025. That’s the number that the report thinks California can reach with a few nips and tucks to its land use policies.

They want cities to identify housing “hot spots,” like places near transit and with vacant lots; make approvals quicker and less complex; promote affordable housing; and reduce the cost of constructing and operating multifamily housing complexes. Again, not exactly news.

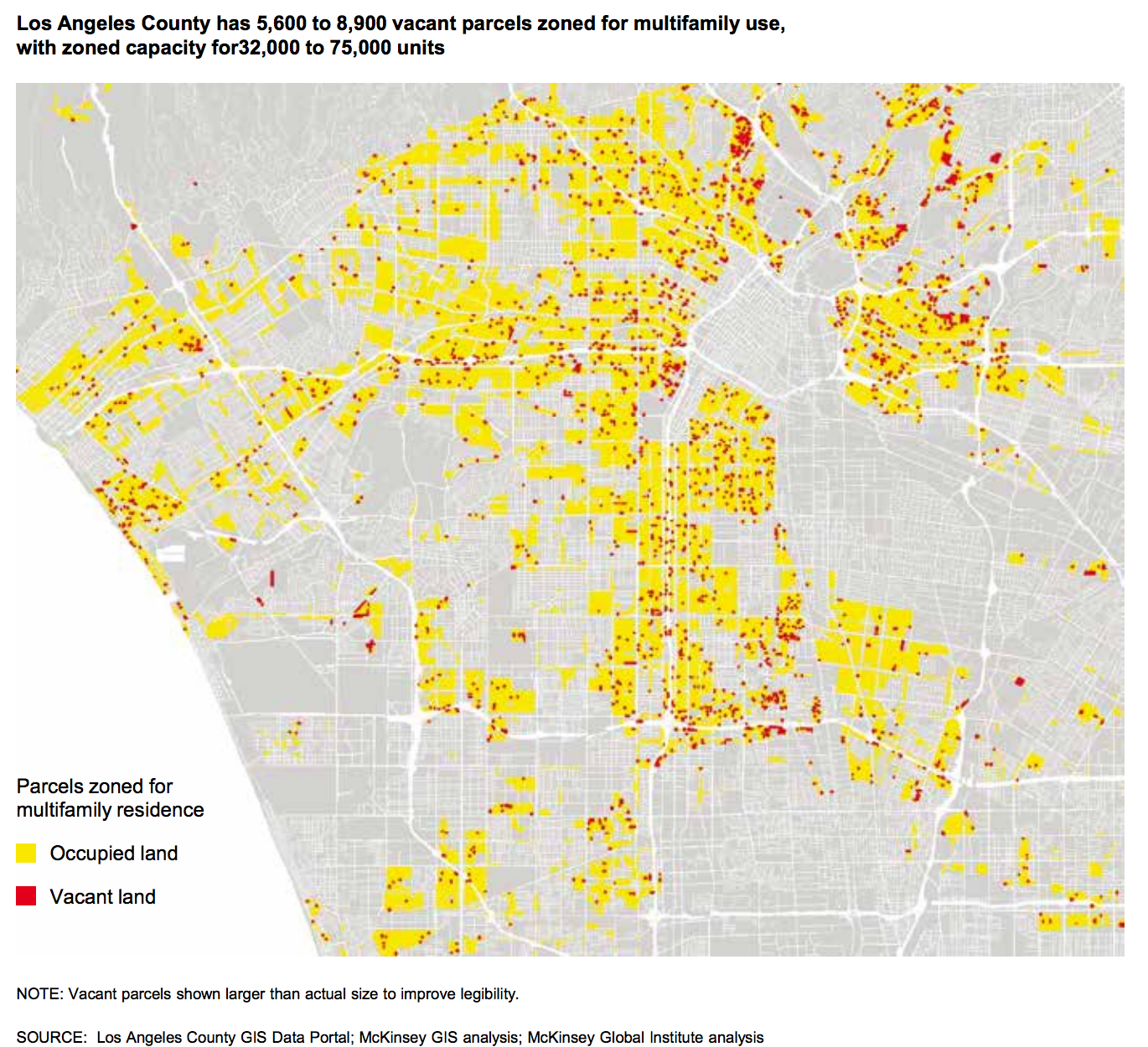

Among the “hot spots," McKinsey estimates that up to 3 million units can be built statewide around transit hubs. The recommendation that has drawn the most attention is that of building on vacant lots that are already zoned for development. McKinsey says there are scads of them in center cities.

Well, of course there are. No one ever said California’s housing shortage was due to lack of land, vacant or otherwise. Planners have been encouraging cities to embrace density for ages. SCAG released its “two percent strategy”, advocating for the region’s future development to take place on two percent of its land, in 2004. McKinsey's recommendation is therefore odd, kind of like saying you should feed the homeless with the burritos in your freezer.

Unfortunately, unless McKinsey is recommending the biggest eminent domain taking in history, the state can’t compel land owners to build so much as a doghouse. Prop. 13 ensures that land owners have nearly zero carrying costs, and California cities don’t have land value taxes.