The California housing market crashed during 2007, and only true optimists and a handful of industry groups predict a turnaround this year. The halcyon days of the housing boom already seem like a long ways away.

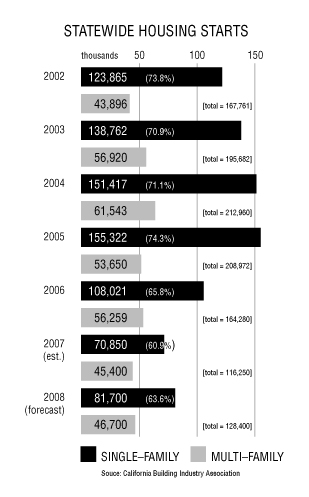

But while the downturn has reached nearly every corner of the state, some markets are stronger than others. In particular, exurban markets are weak, while urban markets focused on infill development are relatively strong. While the single-family market was starting to slip, multi-family construction held steady during 2006, accounting for 35% of all new housing starts, compared with 26% during 2005. Once the final numbers are in, multi-family units may have accounted for as much as 40% of total housing starts during 2007.

According to market analysts, economists and planners, there are number of conclusions to draw, and interesting trends to watch for:

• The downturn has been most significant in what had been the fastest-growing locations, mostly on the metropolitan fringes and in the Central Valley.

• Construction of multi-family units (condominiums, townhouses and apartments) has not fallen off as sharply as single-family house starts.

• Many national homebuilders have bailed out of Central Valley markets that they flooded with new houses as recently as two years ago. These builders are dropping unit prices, selling off land, and not starting new subdivisions.

• Small, infill projects continue to go forward with and without government subsidies.

• A sharp decline in land prices means that some builders are moving toward much smaller houses that are affordable to first-time buyers.

• Entitlement activity is mixed, with some jurisdictions continuing to process as many applications as ever, while other jurisdictions report applications slowing.

• The market has slipped little in desirable locations.

First, a few important numbers: Housing starts for all of 2007 were about 116,000 units — down nearly 100,000 units from the peak of 2004, according to the California Building Industry Association (CBIA). The median price for single-family and multi-family units in California sank to $402,000 in December 2007, according to DataQuick Information Systems — a drop of 17% in less than one year. December was the slowest month for home sales since most outfits began keeping records.

"It's very hard to know how bad this is until we see how far prices are going to drop," said Jed Kolko, an economist with the Public Policy Institute of California. During the recession of the early 1990s, housing prices fell about 20% in the Los Angeles area, he noted. Most of California has not seen a 20% decrease yet, although the California Association of Realtors (CAR) reports prices have dropped approximately 20% in the high desert, the Santa Maria-Lompoc area and the Sacramento region. Interestingly, CAR in October stopped reporting the median price for the San Joaquin Valley, where some builders have taken to auctioning new units. At the same time, prices in Santa Clara, San Mateo, San Francisco and Marin counties have either stayed the same or even increased.

"There is a lot of geographic variation," Kolko said. "There are areas that are much harder hit than others."

"It's pretty amazing what has happened," said Alan Nevin, chief economist for the CBIA. In the industry group's official 2008 forecast released in early January, Nevin predicted a modest uptick in residential building activity, mostly during the second half of the year.

"There is life in spots," Nevin told CP&DR. Downtown San Francisco and San Diego, for example, remain very strong markets, he said.

"We're going to see a lot of new, small projects and, from an aesthetic standpoint, I think that's nice," Nevin said. "All of the guys that got fired by the national public builders have decided to become developers on their own, and they have decided to do small, infill condominium projects."

These projects are typically four to eight units apiece and are located in coastal urban areas, said Nevin, who pointed to several such projects in San Diego. "The difference," he added, "is total value, because all of these little projects in San Diego don't add up to one big high-rise."

While Nevin predicts high-rise condo development will virtually cease in 2008, some jurisdictions — notably Los Angeles , Long Beach and Glendale — have continued to approve new residential towers.

In Long Beach, all new housing is an infill or redevelopment project. In the last three months, developers have completed about 300 units, most of which are for-sale condominiums, according to city Planning and Building Director Craig Beck. More than 800 units of affordable housing are scheduled to come online this year, and roughly 400 to 500 more units of housing supported by the city's redevelopment agency are scheduled for construction over the next 12 to 15 months, he said. The demand for affordable units in Long Beach and almost everywhere else appears limitless.

Of keen interest to Beck and other observers are two luxury condominium towers developed by Intracorp on Ocean Boulevard in downtown Long Beach. Sales have closed on about three-fourths of a 132-unit tower, which was completed in late 2007, Beck said. Intracorp reports that the second, 114-unit tower is 60% "pre-sold." The second tower is scheduled to be complete in March.

"I think they are going to be a very interesting market study," Beck said.

Long Beach is currently processing applications for another 3,500 residential units, only about 100 of which are single-family houses, Beck said. However, developers have withdrawn four higher-end downtown condo projects, including Molasky Pacific's proposed Oceanaire project. With towers of 45 and 55 stories, Oceanaire would have been the tallest buildings in Long Beach.

In some urban locales, notably the East Bay and the Inland Empire, land prices have dropped dramatically. With lots available for $100,000 less than a year or two ago, builders are able to build 1,500- to 2,000-square-foot "starter" homes, rather than 3,000-square-foot monsters that were needed to recoup land costs, according to CBIA leaders. Nevin predicted that very few builders would pursue large speculative tracts and instead would build on an almost custom basis.

"That most certainly in not the M.O. of the major public builders," Nevin said in the CBIA forecast, "but if they want to remain in the state, they will have to adapt to its quirky markets."

During the housing slump of the 1990s, state lawmakers passed a measure automatically extending the life of subdivision maps for two years. The CBIA has requested similar legislation this year. The group is also asking lawmakers to pass a measure permitting builders to delay the payment of impact fees until the certificate of occupancy stage, and to streamline environmental review of new housing. Thus far, the Legislature has shown minimal interest in the CBIA agenda, but that could change if the housing slump drags on.