To many Californians, the streets of San Francisco are what make the city so enjoyable. Some of the best parts of San Francisco are the lively, pedestrian-oriented streets and plazas near transit hubs that blossom with outdoor restaurants, cafes and performances.

But away from these celebrated areas, and despite its scenic hills, San Francisco has many of the same problems with its streets as other aging urban areas. There are countless blocks of treeless roads that are more useful for shuttling speeding cars to freeways, than for providing safe corridors for pedestrians and bicyclists.

The city has set out to improve those streets that don't match up to the city's reputation with an ambitious "Better Streets Plan" that was unveiled in June. Still in a draft form, the 250-page plan will probably get more interesting as specific projects are proposed and San Francisco's notoriously active citizens have a chance to debate what the plan will mean to their neighborhoods and city.

"The plan creates a unified vision for San Francisco's pedestrian environment, which we haven't really had before," said Cristina Olea, of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency and a project manager of the report. (The other major agency involved in writing the report was the city's Planning Department.)

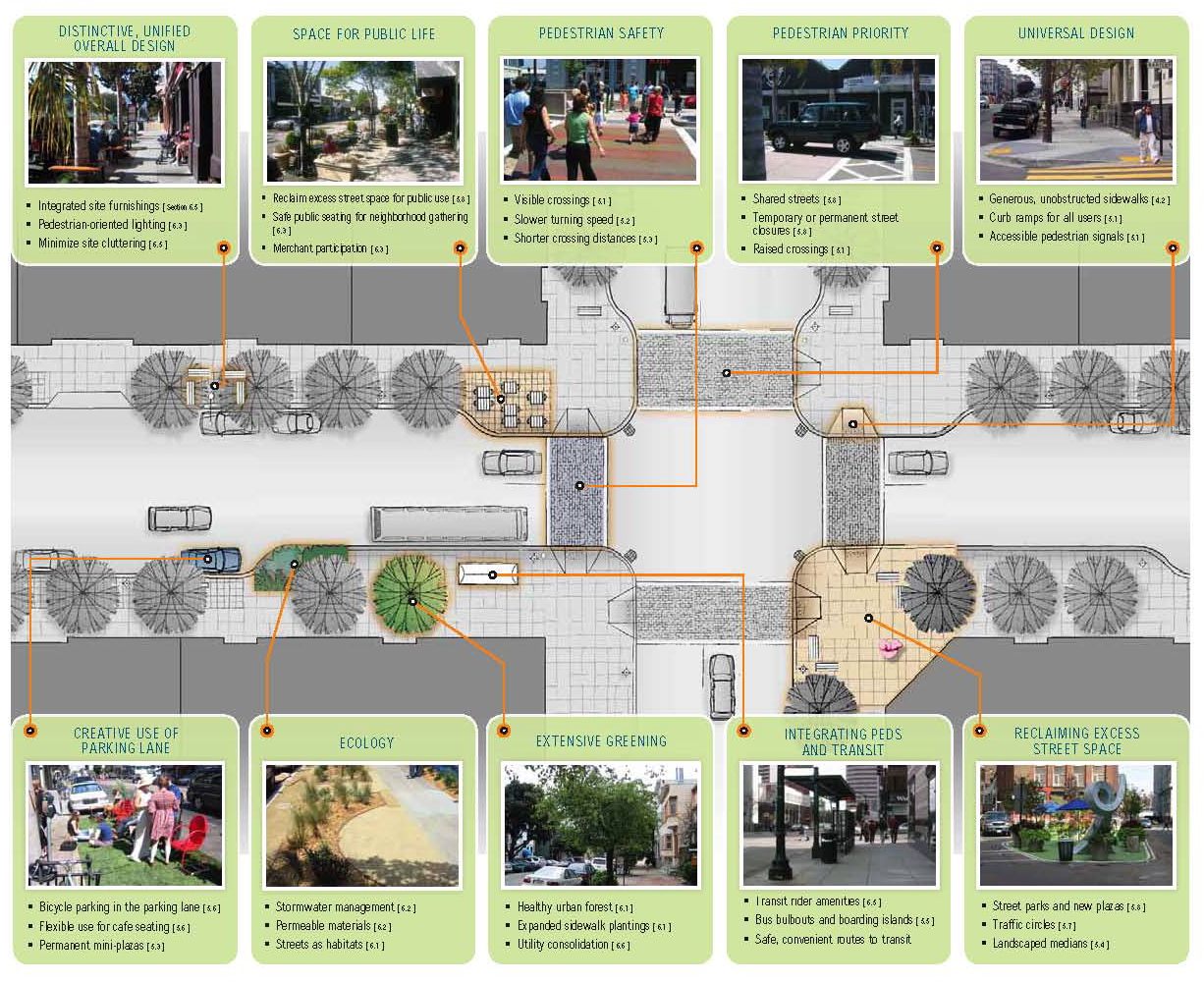

"The plan," Olea said, "includes policy recommendations and design guidelines to improve the pedestrian environment through pedestrian safety, accessibility, streetscape design, and storm water management." Streetscape design, she explained, includes pedestrian-scale lighting, landscaping, and furniture such as benches.

Under the plan, suggested improvements include the addition of landscaped medians separating traffic lanes from sidewalks, more crosswalks, more mini-parks, expanded sidewalk seating for restaurants, and improved ways of collecting rainwater so it percolates into the ground rather than heading for the bay as runoff. Above all, the plan calls for vastly increasing the number of trees and landscaping along the city's streets.

The Better Streets Plan (BSP) notes that many of the city's codes and standards are out of date, reflecting an outdated, single-use vision of the city's streets. "The pedestrian environment is about more than just transportation — the streets serve a multitude of social, recreational and ecological needs that must be considered when deciding on the most appropriate design," according to the plan.

The plan is the result of more than 75 meetings with local residents. "They asked for more landscaping, improved maintenance, more enforcement and street designs that slow vehicle traffic," Olea said.

According to the plan, 20% of all trips made in San Francisco are by pedestrians, while 1% of all trips are on bicycles. The rest are divided between cars and mass transit.

Other planning documents focus on city streets, but Olea said the Better Streets Plan focuses on the pedestrian environment, looking at sidewalks and street crossings.

The plan does not explain what will happen to specific streets, but it categorizes streets by defining land use and transportation characteristics, and suggests changes to each particular type of street, if the city chooses.

The Better Streets Plan makes streets the focus of urban life. That makes sense, say planners, because one quarter of all land in the city lies within the public right of way. That's more land than is found in the city's parks.

Implementing the plan's ambitions, of course, costs money. Plan authors say the city may use state and federal transportation and bond monies to do some of the work. Mayor Gavin Newsom has said some of the money could also come from private foundations. Private property owners would also be expected to play a major role, because most sidewalks are the responsibility of property owners.

The primary focus of the BSP is the area between the curb and building facades, said Jason Patton, who chaired the community advisory committee of the BSP. "It doesn't do much with traffic calming," he said. "The BSP assumes that travelways stay more or less the same."

Although drawings released with the BSP show narrower streets converted with more landscaping and fewer traffic lanes, the plan does not address specifics of how or when these conversions would be done. The BSP does suggest traffic calming ideas such as landscaped traffic circles, as well as temporary or permanent street closures to vehicles, using parking lanes for temporary restaurant seating, and shortening crossing distances for pedestrians. All of these ideas reduce space for cars and increase space for everything else.

"We do want to slow traffic," Olea said, "but the Better Streets Plan does not cover roadway or lane widths."

Some activists think the plan doesn't go far enough.

"Our quarrel is they took urban design to the curb and not out into the roadway," said Tom Radulovich, executive director of a group called Livable City and a member of the Bay Area Rapid Transit District board of directors. "The real danger for pedestrians is in the roadway – traffic speed, traffic volume," he said. The plan "doesn't get into standards."

"The report," Radulovich said, "is a collection of good practices all over the country. It lacks implementation."

Olea said city officials looked at a number of other cities for ideas on street planning, including Cambridge, Mass., Portland, Oakland, Sacramento and Berkeley. Radulovich said other cities doing "bold stuff" with their streets include Chicago, New York and Vancouver.

With its Better Streets Plan, San Francisco joins a national movement to spruce up streets and encourage people to get out of cars, a movement spearheaded by other cities and a national Complete Streets Coalition, based in Washington, D.C. According to the American Planning Association, the complete streets movement "represents a paradigm shift in traditional road construction philosophy. Instead of a project-by-project struggle to accommodate bicycle- and pedestrian-friendly practices, complete streets policies require all road construction and improvement projects to begin by evaluating how the right-of-way serves all who use it."

Newsom recently announced plans to close part of the city's waterfront to cars during two weekends in late summer. As an indication of how difficult it can be to change city streets, that plan was criticized by merchants in Fisherman's Wharf who fear it will harm business during peak tourist season.

The Better Streets Plan also suggests implementing pilot projects, but none has been identified, Olea said. The BSP draft says "high level implementation measures" will be further developed in the next stages of the plan process. The plan needs approval from the Municipal Transportation Agency board and the Planning Commission before it makes its way to the Board of Supervisors for final approval, likely sometime during 2009. The city also needs to complete environmental review of the plan.

Contacts:

Cristina Olea, San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, (415) 701-4579.

Tom Radulovich, Livable City, (415) 344-0489.

Jason Patton, BSP Community Advisory Committee, (510) 238-7049.

Better Streets Plan: www.sfbetterstreets.org