This is a message to all California cities: Take your hats off to Chula Vista. This city of 210,000 people between San Diego and the Mexican border has adopted a plan for an all-new downtown in the Otay Ranch district that makes most other downtown plans seem tentative and incomplete. Perhaps another California community has the political will to approve something equally forward-looking; for the time being, the Otay Ranch Eastern Urban Center is among the plans that are raising the proverbial bar in city planning.

Although the plan, prepared by RTKL's Los Angeles office, is well executed, that plan itself is not the most significant aspect of the prosaically named Eastern Urban Center. The plan, in fact, contains little that is revolutionary or surprising. The real significance here is that the city and the developer, the Oliver McMillin Company of San Diego, actually seem intent on building the thing. In this regard, Chula Vista has an advantage over most other cities in the Golden State (or the state formerly known as golden, before the credit rating agencies noticed we have run out of money).

Otay Ranch is a 5,000-acre project that's been in development for more than 10 years. The Eastern Urban Center, as one might gather, is the intended downtown for this mushrooming community. Much remains under-developed. All of San Diego County is growing quickly, and Chula Vista by itself expects a population of 280,000 people by 2030. In other words, there is enough demand for housing, neighborhood-serving retail and commercial buildings, at least on paper, to make the project feasible.

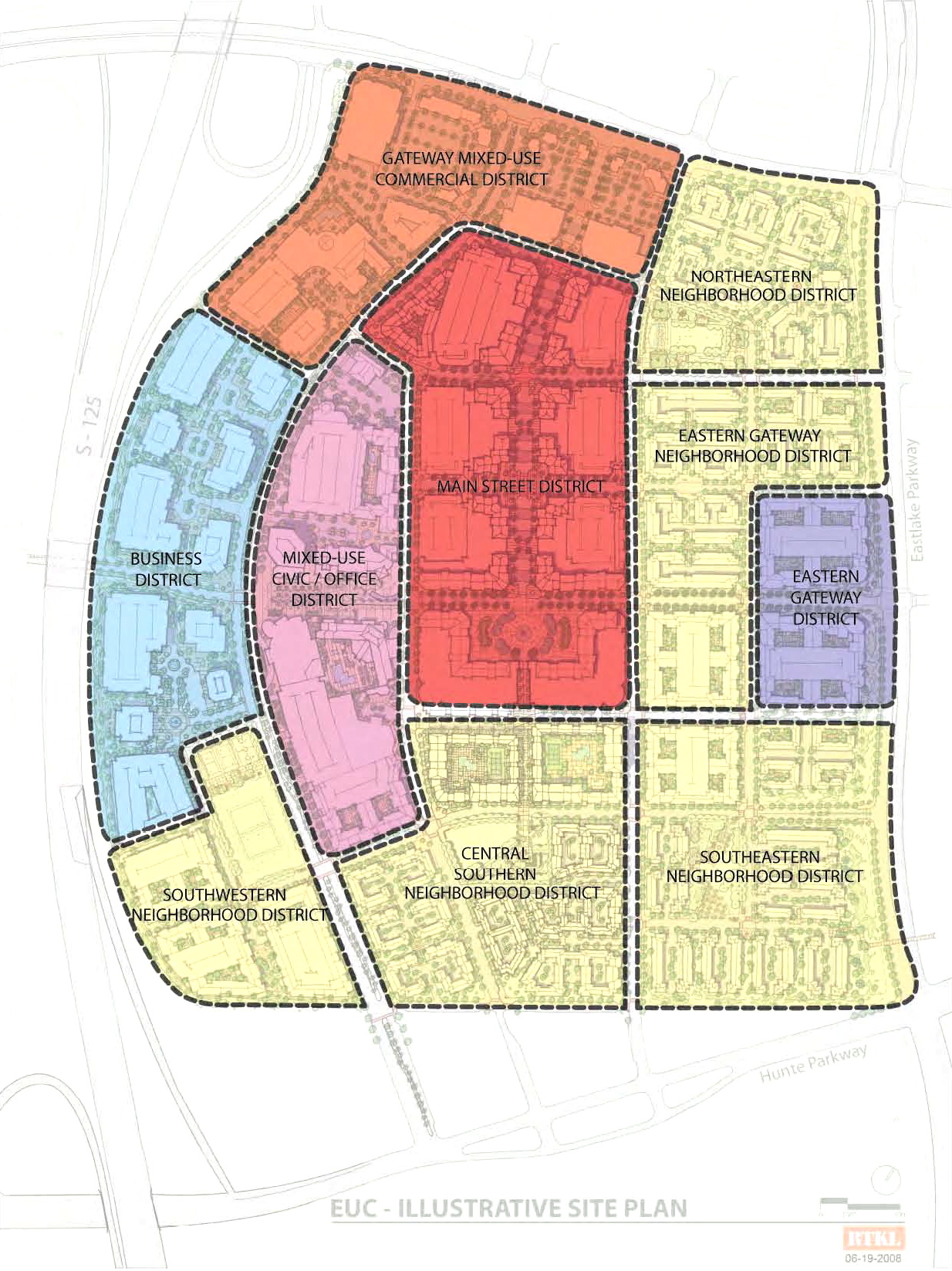

In earlier columns, I've referred to such projects as "instant downtowns." And like many other downtowns, both new and old, the Eastern Urban Center – I refuse to call it EUC or "Uke," – wants to be a residential neighborhood. The plan envisions nearly 3,000 dwelling units, many of them in mixed-use formats. (The high density, mixed-use districts predominate in the upper and upper left-hand side of the map, while the right-hand and lower areas are mostly residential.)

In many ways, the site plan displays some of the features that have grown familiar since the advent of new urbanism and her unacknowledged half-sister, the soft and squishy new urbanism lite that some developers like to hawk to unwary city officials. Like many other plans influenced by recent planning trends, the plan is arranged around a newly minted Main Street replete with parks, mixed-use buildings and retail. Many plans promise pedestrian friendliness; this one delivers. The evidence is the "hierarchy of open spaces" that starts with some sensitively scaled, not-too-large parks and plazas along Main Street and that threads its way throughout the entire project in the form of landscaped sidewalks and trails.

One unusual aspect of the plan is the use of height averaging for multi-story buildings. Instead of imposing a hard-and-fast height limit to any given building, the plan proposes an average overall height, which allows developers some flexibility to build slightly over or under the nominal height limit and density. This is one way to maintain a sense of scale on a given street while remaining attractive to investors.

One possible quibble with the plan is its inward looking-ness. That is, the plan seems to look inward to its own internal Main Street, rather than beefing up commercial development along existing commercial streets, notably Birch Road along the northern edge of the plan and Eastlake Parkway on the east. Nathan Cherry, a vice president of RTKL's Los Angeles office, defends this position by pointing out that the existing streets are essentially suburban strips – a "lifestyle center" surrounded by acres of asphalt is under construction on the north side of Birch Road – and the formality of the Eastern Urban Center would not comport well with the missing teeth and yawning parking lots of informal strip urbanism. It's difficult to achieve a cohensive urban design if planners do not control both sides of the street. Experienced retail developers tend to shun locations that have retail on one side of the street only, because those streets feel unfinished and uncomfortably open-ended. Also potentially discomfiting in the long run is the dramatic difference in both density and scale between the the new downtown and the low-rise, low-density suburbia that surrounds it. In time, of course, we can reasonably expect surrounding neighborhoods to gain density, as well.

One possible quibble with the plan is its inward looking-ness. That is, the plan seems to look inward to its own internal Main Street, rather than beefing up commercial development along existing commercial streets, notably Birch Road along the northern edge of the plan and Eastlake Parkway on the east. Nathan Cherry, a vice president of RTKL's Los Angeles office, defends this position by pointing out that the existing streets are essentially suburban strips – a "lifestyle center" surrounded by acres of asphalt is under construction on the north side of Birch Road – and the formality of the Eastern Urban Center would not comport well with the missing teeth and yawning parking lots of informal strip urbanism. It's difficult to achieve a cohensive urban design if planners do not control both sides of the street. Experienced retail developers tend to shun locations that have retail on one side of the street only, because those streets feel unfinished and uncomfortably open-ended. Also potentially discomfiting in the long run is the dramatic difference in both density and scale between the the new downtown and the low-rise, low-density suburbia that surrounds it. In time, of course, we can reasonably expect surrounding neighborhoods to gain density, as well.

In asking other cities to doff their hats to Chula Vista, we recognize that the real heroes of this plan are Chula Vista's planning staff and elected officials who spent years developing plans for the "Uke" and many surrounding districts. It's one thing to conceive a nice plan; it's another thing for cities to build good plans without destructive compromises. Planning, after all, is about action, not tossing another elegant fantasy onto a pile of discarded plans. Insofar as the current market is dismal, we can only hope that both the city and the developer survive until both commercial space and housing are back in demand. That long wait should give the city enough time to plan carefully—and to come up with a better name than Eastern Urban Center.