[UPDATED APRIL 28, 2014]

The Santa Monica Mountains coastal area, one of the largest still under direct Coastal Commission permitting authority, on April 10 won Commission approval of a Land Use Plan, which was the most significant step toward final certification of its Local Coastal Program (LCP). The Commission will take up the interpretive Local Implementation Plan separately, probably at its June meeting.

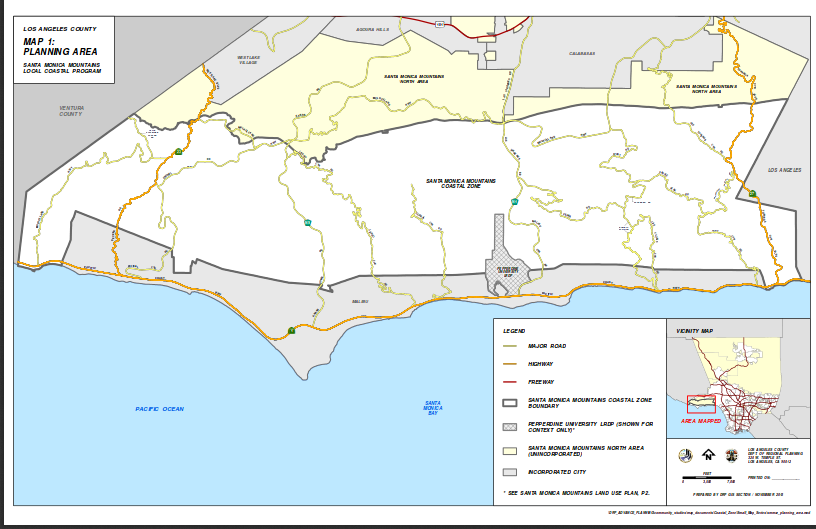

The LCP plan area covers a broad swath of the Santa Monica Mountains inland from the Malibu city limits and Pepperdine University, running approximately five miles to the crest of the mountains and covering 50,000 acres. A further mountainous "North Area" is subject to similar planning approaches but is inland of the Coastal Act's jurisdiction. The area under the Santa Monica Mountains LCP touches the coast only briefly on either side of Malibu's long, narrow strip of coastline. The traditionally fractious City of Malibu has had its own separate LCP since the Legislature forced it to adopt one in 2002.

Final Commission approval for an LCP would delegate coastal permit approval powers to the county, removing a layer of regulatory process from most construction approvals but requiring the county to operate per the Commission-approved plan.

The plan passed the Commission with environmental groups generally in favor and mixed positions by affected property owners, with farmers and vintners most strongly in opposition. A brief political season leading up to the meeting included a letter-writing campaign against the plan's agriculture restrictions.

After a long history of past false starts, the LCP project was reportedly restarted by LA County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, in order to wrap up the matter before the end of his last term as Supervisor. He vigorously cheered the county and Commission efforts to completion. A statement on his weblog after the Land Use Plan certification called it "a vote that will resonate for generations".

Richard Bruckner, director of the LA County Department of Regional Planning, said the Santa Monica Mountains LCP policies, crafted mainly by the County, took a new approach to the usual starting binary for a Coastal Commission permit discussion: whether land qualifies as "Environmentally Sensitive Habitat Areas" (ESHA) or not. He said they worked out "a much more nuanced plan where there are gradations of habitat."

Bruckner said previously each permit application began a negotiation over the extent to which development on a property could be limited without effecting a taking. The new approach would be clearer, hence less time-consuming, he suggested.

The new plan classifies land in three categories of sensitivity, H1 through H3, ranging from severe limitations on development in H1 to relatively relaxed standards in H3 zones that are already developed. Long-term Commission watcher Susan Jordan, director of the California Coastal Protection Network, said the H2 standard applied development restrictions that would be typical of restrictions on development in ESHA areas. Don Schmitz, an organizer of opposition to the plan who frequently represents permit applicants before the Commission, said "I understand it was a hard-fought compromise that was hammered out with the Coastal Commission staff."

The plan allows existing farming and vineyards, and new or old personal gardens. However, it creates a heavy presumption against "new crop-based agricultural uses" and prohibits new vineyards outright, based on concern about runoff, erosion, pesticides, and habitat disruption, especially on steep slopes.

Initial drafts would have prohibited all new "crop-based" uses, but in light of the pro-agriculture campaign, the Commission approved an addendum whose major provisions clarified that not all new crops were prohibited, and described small-scale gardening and farming that could still be allowed if organic and biodynamic methods are used.

Yaroslavsky wrote on his weblog that the Commission added the additional wording about authorized agriculture due to "misinformation" from opponents including Schmitz, whom he singled out by name. In the earlier of two weblog posts focused on the April meeting, he gave a heated defense of the LCP against claims that it would unreasonably restrict property use, especially with respect to crops and animals.

Schmitz in turn accused the plan's creators of failing to observe protections for agriculture that he argued were centrally enshrined in the Coastal Act, and of moving the approval process too fast. He said the original proposal was for an "outright and complete ban on any agriculture in the Santa Monica Mountains," but that he and other opponents were "chastised" for saying so because the proposed rule "magnanimously" would allow existing agriculture to continue.

Schmitz described himself as a farmer and vineyard owner and a spokesperson for a new group, the Coastal Coalition of Family Farmers, which was the plan's most visible opponent as of April. Schmitz said this group was newly formed in response to news of the plan proposal. He said the proposal took farmers by surprise and did not leave much time for them to organize a response.

In an email Jordan wrote, regarding opposition complaints on timing, "all legal time requirements were fulfilled, all sides -- supporters and opponents -- had the same access to information, and were well informed of the direction it was going."

A Change.org petition bearing the logo of Schmitz's group is still posted at http://www.change.org/petitions/local-coastal-program-protect-the-future-of-farming-in-the-santa-monica-mountains. The page introducing the petition refers to "Banning future agricultural land use". The petition had received 922 signatures as of this writing, many added after the April meeting, some from as far away as Nevada, Ohio and Italy.

The Commission staff's 179-page addendum, containing last-minute responses and revisions to the proposal, included letters showing a mix of strongly held local sentiments: support from environmental and community groups and some landowners, and opposition from other local landowners, the Farm Bureau, Pacific Legal Foundation and Malibu Chamber of Commerce. The opponents' letters contained varying phrasing about whether what was to be banned was new farms and vineyards, or agriculture in general.

Bruckner and Jordan said the many established equestrian facilities in the Santa Monica Mountains would be helped to come into compliance before they faced hard-edged enforcement actions. Jordan, herself an equestrian, said descriptions of the help with compliance as an "amnesty" program were, however, inaccurate.

The Santa Monica Mountains LCP process has spanned most of Yaroslavsky's long-running political career. He was first elected to the LA City Council in 1975. The LA County Supervisors took the first step toward an LCP in 1982 by approving a Land Use Plan for the Malibu area. The Commission certified that plan in 1986 but because the Supervisors had not passed zoning and planning ordinances to implement it, the Commission could not approve the whole LCP. The Supervisors partially restarted the process in 2007, then stalled, then recently redid the whole package.

And now, at last, the plan is headed toward final certification, with only the meeting on implementing details to get through, presumably at the meeting scheduled in Huntington Beach in June.

Looking toward June, Bruckner said, "It's the details, but I'm very pleased that... we've got agreement on the policies between the Commission and the County. And I think we can work through the details with the Commission staff. They've been very generous with their time and we've had a good dialogue with them."

The lack of a Santa Monica Mountains LCP was recently an issue in Hagopian v. State of California, discussed at http://www.cp-dr.com/articles/node-3440, in which organic farmers at the top of Topanga Canyon attempted to develop their property based on county approval without going to the Commission. Participants on all sides of the LCP debate declined to comment on the Hagopian matter, all distancing themselves from the Hagopians' position that the LCP had not been needed at all.

Bruckner said he anticipated the LCP would bring the county about 30 to 40 new permitting cases a year, depending on economic conditions, and then there would be work to do with nonconforming property owners. He said "by the commission staff's own reckoning there are as many violations or unpermitted improvements in the Santa Monica Mountains as in the ... rest of the coastal areas combined."

While the new Santa Monica Mountains LCP may transfer that much workload off of the Coastal Commission, it won't be as much of a change as in 2002. That was when the Commission, under orders from the Legislature's AB 988, created and approved an LCP for the City of Malibu, ending a long tradition of extended fussing over Malibu local issues at meetings of the statewide body. Some of the history is explained in Malibu's LCP, as created in 2002, appearing as an attachment to the September 2002 agenda at http://coastal.ca.gov/meetings/mtg-mm2-9.html. Conoisseurs of legislative dudgeon may appreciate the last three staff analyses on the 1999-2000 session's AB 988, available at http://bit.ly/PK0b0V.

Links:

Malibu Times: http://bit.ly/1p0Wg0a

Thousand Oaks Acorn: http://bit.ly/1lZfLR5

LA Business Journal: http://bit.ly/QTS4Qn

LA County LCP planning page: http://planning.lacounty.gov/coastal

Yaroslavsky's weblog: http://zev.lacounty.gov/news/a-high-note-for-mountain-protections

For a list of coastal segments where Coastal Commission permit authority had not yet been transferred as of November 2013 see http://www.coastal.ca.gov/lcp/LCPStatusSummFY1213.pdf.

Coastal Commission April agenda, annotated with results, LCP documents attached: http://coastal.ca.gov/meetings/mtg-mm14-4.html

Monterey Bay Shores Resort

The Coastal Commission approved developer Ed Ghandour's proposal for the 39-acre, 368-unit "Monterey Bay Shores Resort" in Sand City, which has been before the Commission intermittently since 1998. The decision overrode intense objections from environmental groups and agencies that had sought stronger habitat protections for species including the Western Snowy Plover, Smiths Blue Butterfly and Monterey Spineflower.

The approval used a special procedural double play to wrap up the case both in an appellate court and at the Commission. At the start of the three-day session, the Monterey resort proponents -- formally, Security National Guaranty, Inc., or SNG -- were close to settling 13 years of litigation with the Coastal Commission. SNG had won a ruling in San Francisco Superior Court that the Coastal Commission appealed. Before going forward with appellate briefing, the parties agreed to seek resolution of the matter in a hearing of the Commission with the option to return to court. The matter was set to recur on the April 9, 10 and 11 agendas so the Commission and courts could act in correct order to sew up the settlement.

The Commission heard environmental objections, centered on the plover habitat issue, from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, California Parks & Recreation Department, environmental organizations and individual objectors, while local officials praised the project's design and potential economic benefits. Other issues included measures to reduce bluff erosion; provide stability for the structures, which would be built on a dune field; preserve views from Highway 1, and protect surrounding sand dunes. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had called for SNG to prepare a habitat conservation plan and apply for an incidental take permit. The primary environmentalist objection was that instead the final plan called for created a "habitat protection plan" with fewer enforceable specifics.

Having reached a settlement, the parties dismissed the court cases and returned Friday, April 11 for an approval decision. When it was time for the approval, the Monterey Herald said it took four minutes.

Links:

Monterey Herald on the start of the debate: http://bit.ly/1qu4jzR

Monterey Weekly blow-by-blow on the marathon April 9 debate: http://bit.ly/1klDagR and on the outcome: http://bit.ly/1gXQu5A

Monterey Herald looking toward the April 11 post-settlement approval: http://bit.ly/1hEpbgG

Herald on the final approval: http://bit.ly/OZbodM

Audubon Society "displeased" with the habitat provisions: http://bit.ly/1qW4F0E

The Sierra Club likewise: http://bit.ly/1enOKb2

Appeal of Security National Guaranty v. CA Coastal Commission, settled April 10, as shown on the online docket at http://bit.ly/1kVsyUh

Related San Francisco Superior Court dockets; many more recent papers are downloadable: http://bit.ly/1lYcVgb; http://bit.ly/1lYg5AC.

(Disclosure: the judge in the San Francisco Superior Court case, Harold Kahn, heard an unrelated matter in March in which Martha Bridegam participated as an attorney.)

Paradiso Del Mare approval disappoints Surfriders

The Commission approved the Paradiso Del Mare proposal for two large private homes on Brooks Street in Santa Barbara County west of Goleta, sought by CPH Dos Pueblos Associates. The approved proposal provided for coastal trail and habitat restoration mitigations including $500,000 "for public access trail implementation" and $20,000 for a new "Seals Watch" volunteer group, but local environmental activists condemned them as insufficient or even harmful.

The 454-page official record includes statements that 137 of 143 acres on the project site would be "preserved as permanent visual open space," of which 117 acres would be preserved as habitat, with "substantial public access and recreation easements on the property representing the first phase for implementation of the California Coastal Trail along the 20-mile Gaviota Coast."

Local Surfrider Foundation chapter chair Mark Morey wrote indignantly to supporters that the 7-4 vote to approve the project "was a vote against you, the community, nature, and the Gaviota Coast." He wrote that surfers and the larger public would lose beach and trail access, a white-tailed kite nesting tree would be affected, and other private development projects would likely follow these first two. (Objections to the project in the prior record include arguments that although the project was approved to include only two residences only, it would create conditions that make nearby land easier to develop.)

In an email exchange, Morey and fellow Santa Barbara Surfrider members wrote that the construction would block a trail that "has been used by the public across private land for around 50 years" and would replace it with an access easement that, to become a trail, would depend for its construction costs on county or other third-party funds. (Objections noted in the record said a trail on available easement routes would call for a stairway costing $750,000 or more.)

Further, the Surfriders objected that the project would be built close to a seal rookery, and the expected easement route would likely run so close to the seals that it might have to be closed during the season when both seals and surfers traditionally used the area. The chapter's Bob Keats wrote that future occupants of the project would have access to the seals' area any time, "in contrast to the infrequent access to the beach by surfers, as the surf, although high in quality, does not occur very often."

Keats questioned whether adequate notice had been given of amendments to the commission's settlement with the developer that, when they were discussed at the meeting, seemed to persuade some commission members toward approval.

An account posted April 15 by the Santa Barbara Independent said some Commission members were startled to be presented with revisions to the settlement agreement during the meeting and that Commissioner Mary Shallenberger raised questions about notice.

Surfrider and the Gaviota Coast Conservancy are plaintiffs in a pending court challenge to the EIR. On the case, Morey wrote, "every option is on the table." Keats wrote that the suit would now name the Coastal Commission as well, "and we will continue to pursue the litigation."

Santa Barbara Independent reports: April 8: http://bit.ly/RgI7gF; April 15: http://bit.ly/1kXRMWx

The local Noozhawk site on the court case: http://bit.ly/1kmfWa9

In other Coastal Commission news:

- The Commission unanimously disapproved the Beach Plaza Motel teardown and reconstruction on Ocean Blvd. in Long Beach. The Long Beach Press Telegram reported the Commission found the proposed swankier replacement would violate a Local Coastal Program provision "to "protect access to the coast for people of low and moderate incomes."" The plan had been opposed by UNITE HERE Local 11, environmentalists and neighbors. For the Press Telegram report see http://bit.ly/1khfQk8. The Long Beach Post has more at http://bit.ly/1m59CUD.

- Santa Monica received Coastal Commission approval, with conditions, to replace the deteriorated 84-year-old California Incline Bridge, Ocean Avenue to PCH, with bluff stabilization, better structural stability and improved sidewalks and bike lanes. The project is expected to close that heavily used link between the PCH and Ocean Avenue for 12 to 18 months.

- The Commission approved revised findings in a staff report in support of a disputed athletic fields renovation in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. Some neighbors have opposed the use of artificial turf, bright lights for night games, and the resulting loss of informality at that end of the park. Others have endorsed the same choices. The City Fields Foundation, which supports the renovation, posted on Facebook at http://on.fb.me/1eo8Txv, "Though just an administrative action, this vote was critical if we are to start construction this spring." As reported in the San Francisco real estate blog Socketsite at http://bit.ly/1hDliOM, the Coalition to Protect Golden Gate Park is gathering signatures for a ballot measure against the renovation.

- To the Surfrider Foundation's joy, the Commission approved a proposal to truck in extra sand to replace erosion at Broad Beach in Malibu. Malibu Times: http://bit.ly/1kVNpGW; Surfrider Foundation: http://bit.ly/1m0NahW

- Items noted at the meeting as not requiring a coastal permit included an emergency dust control project at the Oceano Dunes State Vehicle Recreation Area.