The Santa Ynez Valley in Southern California brands itself as bucolic wine country, a mix between grape-covered hills and Old West charm. The Chamber of Commerce touts the hospitality and diversity of the valley's few thousand residents, but one thing that isn't mentioned in the Chamber's materials is the Chumash Casino Resort, a business run by the government of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians that made a reported $366 million in revenue in 2008.

The government of the Tribe, which claims 249 on-reservation members, is attempting to acquire relatively autonomous federal trust status for a greater proportion of the Tribe's historic land. The Tribe's representatives believe that they have the finances and a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision in their favor. The local government and state officials, however, have allied themselves against the proposal for fear that added Tribal land development may upset the power balance in the valley.

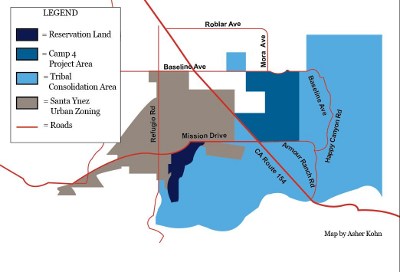

The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians have been given claim to 15,000 acres of Tribal Consolidation Area – that is, title to land claims too small or of too obscure title in their individualities to be apportioned to any individual Tribal member. If the Tribe acquires full fee-simple title to property in this area, it can apply to have it taken into trust. Within the Tribal Consolidation Area, the Tribal government has purchased and is seeking trust status for a 1400-acre property on Highway 154 near Solvang. The property is a subdevelopment of the former Fess Parker vineyards called "Camp 4," currently zoned for agriculture and partly planted in grape vines. (See http://www.kitawines.com/vineyard/.)

The Tribe's announced plan for the land is to develop housing for members. Many non-Native residents and state and county officials, however, are worried that the land could be used for economic development projects outside the reach of taxation or regulation. (Local opponents' sites include http://polosyv.org and http://www.syvconcernedcitizens.com/.)

A long-disputed claim

Tribal developments can avoid state and local regulations because tribes are outside states' jurisdiction. Native American tribes are recognized by the federal government as separate sovereigns, often with treaty rights recognized and signed by various U.S. Presidents over the years. The Santa Ynez Reservation was established in 1901 and has been the site and focus of litigation ever since. (For an introduction to prior Chumash history see http://www.santaynezchumash.org/history.html.)

Revenues from the Chumash-owned casino are a particular thorn in the side for local non-Indians who perceive the casino as both a competitor for tourist dollars and a magnet for crime. A California compact with the Indian reservations within the state to regulate tribal gaming was approved by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 2000. It provides the framework to define what kinds of gaming are allowed on reservations such as the Chumash's and how the revenues may be used.

The casino business has been good for the Chumash, seeing as their reservation is only 125 miles from Los Angeles. The Tribe has been able to purchase land from Santa Barbara County and various landowners that had fallen out of Tribal authority 80 years ago. Now the Tribe is hoping to use either an administrative BIA process or a Congressional bill introduced on its behalf (HR 3313) to turn this purchased land into Federal land held in trust for the Tribe.

Under trust status, the federal government would hold legal title, unattachable to tribal mortgage or debt, explicitly for the benefit of the entire Tribe and outside the state regulatory framework. "Trust" land has been held to be more purely "Indian Country" than land held by a tribe in fee simple. So state officials are concerned that if the land becomes trust land they will no longer be able to keep the Tribe from using it however it wishes – possibly building high-rise or high-density apartments against local zoning ordinances, or even constructing casino expansions.

Although HR 3313 explicitly excludes gaming from the acres at issue, the tribe's opponents are worried that this express statement could be overridden by later law once the land is out of state hands. Andi Culbertson, a Santa Ynez Valley resident and land use lawyer, said there is "hardly a necessity for housing" for those Tribal members who live in the Valley. (How many are full-time residents is disputed.) Culbertson expresses concern that once the land is solely in Tribal hands, "they can build anything."

In order to to stave off this particular eventuality, Santa Barbara County has chosen not to negotiate release from local to federal control of the 1400-acre plot at issue – confident that HR 3313 will not pass Congress.

The Chumash Tribe has proposed to make payments to the state and county in lieu of taxes. (Tribes do not pay taxes to states, as sovereigns of equal standing.) The Tribe has also offered to limit its tribal sovereignty by allowing County participation in the planning process. "In a perfect world, tribes and their counties would work out some agreed-upon system similar to currently existing county LAFCO processes," said Sam Cohen, the Tribal spokesman and a lawyer for the Santa Ynez Band. According to him, such a system would allow for "counties to get the early warning they desire and tribes and counties could reach agreement as to some of the jurisdictional conflicts."

However, Santa Barbara County has successfully created an impasse where Congress, at the suggestion of the District's Rep. Lois Capps (D-Santa Barbara) is waiting to see a local agreement that the County is unwilling to undertake. (The sponsor of HR 3313 is not Capps, but Rep. Doug LaMalfa, R-Richvale. See http://lat.ms/1nJcrN1.)

At the same time, the office of the California Attorney General has taken a generally negative view of the fee-to-trust process, issuing comments to be attached to public records of various California tribes' fee-to-trust applications that attack "the very foundation of the federal statutes authorizing land in trust acquisitions, fostering discord and misunderstanding between tribal Nations and the State of California" in the words of Robert Smith, chair of the Pala Band of Mission Indians. The Attorney General's office points to the tribes' lack of interest in agreeing to waivers that the AG has sought. These would provide that fee-to-trust lands would "only serve on-reservation uses and that the Tribe waive its sovereign immunity to allow for enforcement of that condition." Such commitments would presumably make for neighborliness but are not legal requirements for tribal action.

The opposition to the Chumash plans comes from a variety of sources, but focuses on a few key issues summed up by the California Coastal Protection Network. The Network notes that although 100% of the 111 California fee-to-trust applications to the Pacific Region of the Bureau of Indian Affairs from 2001-2011 were approved, those each averaged under 100 acres, far smaller than the Chumash Tribe's application for 1,400 acres. The Coastal Protection Network also decries the vagueness of the Tribe's offered Cooperative Agreement, saying that it "did not contain an explicit project description for uses on the 1400 acres, but indicated that it would include housing and unspecified ‘economic development'." By the Network's reasoning, a larger project such as Camp 4 would call for disclosure of more complex plans than a hundred-acre plot in a less economically valuable part of California. But the Tribe is reading the guidelines for fee-to-trust applications as more permissive than what opponents would like to see.

Tribal land is not subject to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). While this would seemingly allow for massive development opportunities, in practice tribal authorities follow the spirit, if not the letter, of local environmental quality acts. This is partly because tribes are still subject to federal environmental standards. Also because tribes, which often need to make the best of reservation areas that are only a fraction of their original suzerainty, have a political interest in sustaining the land they own.

The trend of tribal action generally aside, Culbertson notes that "It's a developer's fondest dream to be able to escape all state regulations," and the Camp 4 development would do precisely that.

Culbertson emphasizes that the county's tax base and regulatory control would be weakened by the fee-to-trust transfer. Santa Barbara County is currently suing the Tribe over a breach of the Williamson Act (an agricultural property tax break for conservation purposes), claiming that the Tribe never filed the application on which it has been relying for tax breaks, instead relying on the former owners' application. Cohen, representing the tribe, claims that the suit is largely procedural and says he believes the assertion is largely "that we haven't done it fast enough." (See http://bit.ly/1pl6plF.)

The comment process on the Tribe's Environmental Assessment for the fee-to-trust plan, filed with the BIA under the federal National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), closed on July 14. (See http://www.chumashea.com/.)

A precedent for others?

While the claims ultimately come down to mutual distrust and glares across the state/federal divide, recent changes in state and federal law raise the stakes for the Santa Ynez Valley dispute and may turn its outcome into a precedent.

California's worsening drought has exacerbated water ownership issues throughout the state's water basins. HR 3313, the Congressional bill to authorize the land's transfer to trust status, attempts to bifurcate the tribe's sovereignty claim from its water issues. It explicitly would not "affect any water right of the Tribe in existence before the date of the enactment of this Act." (For the text and status see https://beta.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/3313.)

Despite this legislative buck-passing, legal scholars believe that because the Reservation was created in 1891 – and because the creation of the Reservation reserved rights inherent in the Tribe since pre-contact – the Chumash Tribe has a right to water in a first-in-time system dating back to at least the 19th century and perhaps time immemorial. Although this right is ostensibly only to Zanja de Cota Creek, the creek has since dried up and its connected groundwater can be employed by the Tribe to fulfill the purposes of an Indian reservation, according to a related Ninth Circuit case concerning the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe in Nevada, United States v. Orr Water Ditch Co., 42 ELR 20252 (9th Cir., 2001).

In a 2013 article studying the Santa Ynez Tribe's case in the West Northwest Journal of Environmental Law & Policy, Joanna "Joey" Meldrum (then a new UC-Hastings law graduate; now a land use attorney with Holland & Knight) reflected a widely held view in arguing that, under locally applicable law, "the [Chumash] Tribe should have the right to withdraw as much groundwater as is necessary for the Reservation and its people to survive and prosper," with the Tribe able to receive much judicial deference. (See http://bit.ly/1nMEAV6.)

However, Cohen has downplayed these rights on land outside the reservation proper, saying the priority date on newly-minted Trust land will be "the date that the land goes into trust. Our 1400-acre parcel has a priority date of whenever the land is turned in to the federal government," presumably when the Fee-to-Trust application is approved and title is quieted in late 2014.

The Tribe's dormant opportunity to control water in the Santa Ynez Valley only allows for on-reservation water usage, but it still may give the Tribe the opportunity to control further development, an opportunity that state and local officials perhaps fear.

The state of California's concerns over losing water rights and control over development may be sharpened by a May 2014 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Michigan vs. Bay Mills Indian Community, in which the Court held 5-4 that the state of Michigan could not issue an injunction against Tribal activity (in the Bay Mills case, the operation of a gaming facility) on non-Tribal land. (See http://bit.ly/1nOfB2c for a SCOTUSBlog analysis.) This holding, which may yet be narrowed by further holdings, would seem to allow Tribal governments to countermand any orders state courts might issue to cease development, even on non-Tribal land. The chance to build first and make agreements with the state later would be an enormous opportunity for tribes to operate on an equal footing with states and may even – if Bay Mills is held broadly – reverse some of the many state encroachments on tribal sovereignty that have marked the history of Indian country.

The current standoff between the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians and the non-Native regulatory powers is, in one sense, a local power struggle determining what the base of economic power will be in this hilly Pacific wine country. In another sense, the outcome will determine how much strength tribes will have throughout California in proposing new developments, including housing and businesses.

If the Chumash are able to successfully maintain their rights to land and water they may be able to exert greater control in the Valley and set a precedent allowing for tribal sovereignty-based engines of economic development to sprout throughout rural California. Tribal claims to water and to freedom from state judicial interference are looked at – either enthusiastically or skeptically – throughout the state, and threats of litigation loom over the current-day impasse in negotiation. The current power balance in the Santa Ynez Valley in particular, and in corresponding situations throughout California, has longstanding beneficiaries. Historically disadvantaged groups such as the now-powerful Santa Ynez Band may be looking forward to disrupting those interests through their own avenues of economic growth in the near future.

Asher Kohn is a writer and law school graduate based in the Bay Area. He writes about land use and disuse. See www.asherjkohn.com.